The significant response to Victoria’s working from home reforms suggests that Victorians who can reasonably perform their duties remotely will be entitled to work from home at least two days per week. For many organisations this will formalise what is already happening, with over a third of Australians working from home regularly[1].

This is a massive win for many sectors of the workforce including primary carers, mothers of young children and people with an impactful health condition who are shown to have better employment rates with the capability to work flexibly[2].

Though on the back of these potential changes it is worth exploring whether working from home effectively supports our safety and wellbeing.

Goodbye to the daily commute

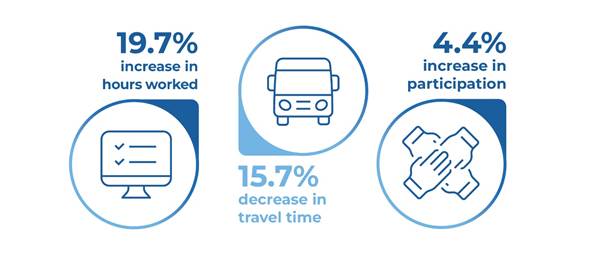

A report from the Committee for Economic Development of Australia (CEDA) calculated that on average workers spend 3.4 hours less time commuting each week[2]. Commuting less brings saving on public transport fares and fuel costs. Time saved can offer greater control over working schedules, making it easier to combine and balance work commitments with non-work activities, including exercise and longer sleep[3].

Are we replacing this saving by working longer hours?

Within the same report from CEDA it highlights that people working from home on average work an extra 5.5 hours more per week. It appears that on average the time saved by not commuting is being replaced by working longer hours.

Stepping less, sitting more

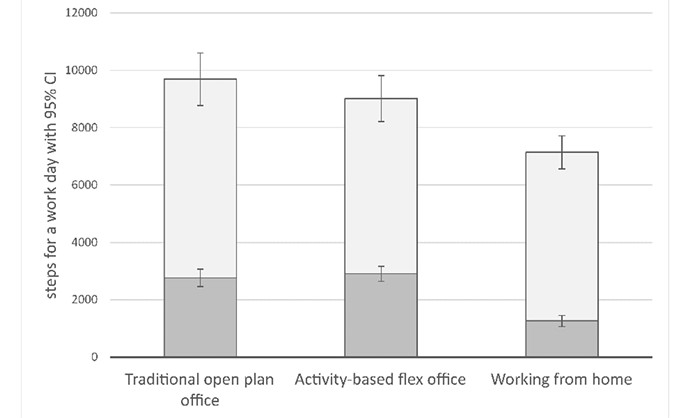

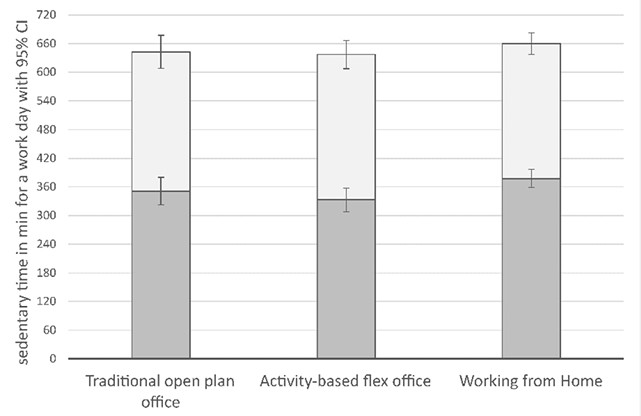

Several studies have found that on average working from home leads to sitting longer and stepping less. One study found that during work time workers walked on average about 2900 steps at the office but only 1300 steps when working from home whilst sitting 46 minutes longer at home. When calculating total daily steps, people working from home would complete about 2000 fewer steps[4]. This step count reduction is significant whereby a positive association exists between a reduction in 2000 steps or more and all-cause mortality, cardiovascular incidence/mortality and cancer incidence/mortality[5].

Source: Sedentary behavior of office workers in different working environments: Sauter et al.

Positive and negative psychosocial factors

Working from home, like all work, brings with it exposure to psychosocial hazards. Increased time spent on screens, longer working hours and blurring the boundaries between home and work can contribute to role overload, a psychosocial risk factor in the development of burnout and fatigue[6,7,8]. Palumbo [9] found that whilst fatigue related to commuting and travelling to the office are reduced when working from home, this does not outweigh the negative impacts from the blurring of boundaries between work and home.

Work-related stress can occur when employees are exposed to psychosocial risks. There are mixed findings when reviewing working from home and the risk of work-related stress. For some, working from home can lead to an increased risk of stress due to role conflict, increased workload, lack of communication and difficulty balancing work and family[10]. Additionally, working from home can also increase stress related to excessive technology use[11]. Conversely some studies have noted a reduction in work-related stress when working from home due to factors such as increased work autonomy, less distractions, and not having to commute[12]. Autonomy is an important element of working from home because it provides employees with the opportunity to make decisions about different work tasks.

Whilst the pandemic and lockdowns may have influenced a lot of the research and challenges faced by people in the early 2020’s, loneliness and social isolation remain a significant concern. Pre-pandemic research also showed home workers reporting more feelings of social and professional isolation than their office-based counterparts. Young workers, those living alone, people with poorer general health and those with less self-discipline are also more likely to experience difficulties related to loneliness, social isolation and networking when working remotely. A lack of support from colleagues and managers, and lack of job autonomy are significant factors influencing loneliness amongst remote workers[13,14]

One study identified that working from home activates job resources like flexibility, increasing job satisfaction, whereas it reduces job resources such as social support that can lead to feelings of loneliness the longer a person works from home. After four years, the positive effect of working from home vanishes which is explained by rising feelings of loneliness that contradict satisfaction with flexibility in the long run[15].

Fulltime workers or long-distance commuters may value flexibility, while new joiners or single-household employees might prioritise socialising, networking, and gaining information. Thus, the effect of working from home on outcomes such as job satisfaction may be moderated according to a group’s preferences for flexibility and interaction and should be considered within a temporal framework.

Working from Home Ergonomics

The physical environment is another important consideration. A poor environment can lead to increased risk of negative physical and mental health outcomes [16,17]. A study of over 40,000 Dutch workers found that employees working from home or in hybrid arrangements had a higher self-reported pain in the upper back, neck, shoulders, and/or arms compared to those working on location. The risk was also higher for those working exclusively from home compared to hybrid [18].

Not having a dedicated or appropriate workspace or workstation can increase pain, discomfort and the risk of musculoskeletal injury as well as exacerbating existing injuries [16,17,19]

A US survey of almost 1,000 people working from home found that respondents who reported having a good workstation set-up for their health, wellbeing and productivity, and knowledge on how to adjust it, were less likely to report experiencing new physical and mental health issues after commencing working from home arrangements [17]. This is especially concerning since young employees or those from a lower socioeconomic status might be more vulnerable to poor ergonomic working conditions in their homes and have less economic incentives or knowledge of possibilities to adjust them.

These findings demonstrate the importance of ensuring workers have an appropriate workstation when working from home, especially since some workers do not routinely monitor and adjust their work environment at home [17,20]

Controlling the ‘place of work’ risks

As working from home is defined as the ‘place of work’ the same statutory tests apply as with any other workplace. Office workplaces have typically gone through a rigorous process to ensure risks associated with the work environment have been controlled and managed. The need to adequately identify, control and manage the working from home environment requires the same rigour, and one that is often overlooked by many workers and organisations. Our WFH Ergo Safety Program data shows that over a third of people working from home do not have access to a fire blanket or fire extinguisher.

Completion of a checklist alone when commencing work from home fails to constitute sufficient risk management and this has been proven many times when contesting liability for work injury claims. In one case the Magistrate noted that whilst a checklist demonstrated the Employers attempt to guard against work health and safety risks arising from home-working, it had otherwise “abrogated all responsibilities for providing and maintaining a safe environment when working from home”[21].

What is implied here is that more needed to be done to as part of broader initiatives to identify work-from-home hazards. These could include:

- Provide advice to employees regarding the ergonomic set-up of home workstations and/or risk assessments.

- Review outcomes or findings of checklists, ergonomic and/or risk assessments with employees to ensure appropriate controls are in place.

- Encourage employees to report any concerns and problems promptly and letting them know how to do so

- Re-assess the working from home environment periodically or as the environment changes.

Summary

Working from home and hybrid arrangements have led to new work health and safety concerns for workers. There is a potential that, if not well controlled, working from home can impact workers’ wellbeing and safety with known risks including musculoskeletal pain, injury, burnout, fatigue, social isolation, health decline and work-related stress.

Well-managed working from home however can have a positive influence on workers’ lives in relation to reductions in time, cost and stress associated with commuting, greater autonomy over when and where to work, and an improved ability to manage work and personal demands. It engenders an inclusive culture enabling employment for more sectors of the workforce.

To leverage these benefits, strategies must accommodate individual differences and acknowledge the multiple intersecting personal and professional roles and obligations that workers take on. Leaders should also be aware that personal characteristics such as being young, a woman, a new recruit, having carer responsibilities, living alone, lower socioeconomic status or being in a lower-level role can make workers more vulnerable to some of the risks associated with working from home or hybrid arrangements.

To address this, employers need to focus on setting effective systems and frameworks that support safe and healthy arrangements and ensure certain groups are not disproportionality affected. Regular review and adjustments to arrangements may be necessary to sustain its positive effects on job satisfaction. Although they may have less control over the workspace, employers can still influence and provide tools for workers and managers to support themselves. Workers will always have a duty to take reasonable care for their own health and safety and should continue to assess how hybrid arrangements may affect them and work with their employer to design and maintain a healthy balance to hybrid work.

References

1. Australian Bureau of Statistics. “Working Arrangements”, August 2024. https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/labour/earnings-and-working-conditions/working-arrangements/latest-release#workingfrom-home

2. CEDA (2025), “Working from home is saving Australians time and money”, 2025. https://cedakenticomedia.blob.core.windows.net/cedamediatest/kentico/media/research-team/reports/ceda-data-insight-wfh-commute-2025-final.pdf

3. Massar, S. A. A., Ong, J. L., Lau, T., Ng, B. K. L., Chan, L. F., Koek, D., Cheong, K., & Chee, M. W. L. (2023). Working-from-home persistently influences sleep and physical activity 2 years after the Covid-19 pandemic onset: a longitudinal sleep tracker and electronic diary-based study. Frontiers in psychology, 14, 1145893. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1145893

4. Sauter, M., Backé, E., Pfab, C., Prigge, M., Brendler, C., Liebers, F., von Löwis, P., Pfeiffer, A., Papenfuss, F., & Hegewald, J. (2025). Comparison of sedentary time, number of steps and sit-to-stand-transitions of desk-based workers in different office environments including working from home: analysis of quantitative accelerometer data from the cross-sectional part of the SITFLEX Study. Scandinavian journal of work, environment & health, 51(4), 333–343. https://doi.org/10.5271/sjweh.4228

5. Del Pozo Cruz, B., Ahmadi, M. N., Lee, I. M., & Stamatakis, E. (2022). Prospective Associations of Daily Step Counts and Intensity With Cancer and Cardiovascular Disease Incidence and Mortality and All-Cause Mortality. JAMA internal medicine, 182(11), 1139–1148. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2022.4000

6. Meyer, B., Zill, A., Dilba, D., Gerlach, R., & Schumann, S. (2021). Employee psychological well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic in Germany: A longitudinal study of demands, resources, and exhaustion. International journal of psychology : Journal international de psychologie, 56(4), 532–550. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijop.12743

7. Oakman, J., Kinsman, N., Stuckey, R., Graham, M., & Weale, V. (2020). A rapid review of mental and physical health effects of working at home: how do we optimise health?. BMC public health, 20(1), 1825. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-09875-z

8. World Health Organisation (WHO) (2022), Occupational stress, burnout and fatigue, accessed 11 September 2025.

9. Palumbo, R. (2020). Let me go to the office! An investigation into the side effects of working from home on work-life balance. International Journal of Public Sector Management, 33(6–7), 771–790. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJPSM-06-2020-0150

10. Hayes, S. W., Priestley, J. L., Moore, B. A., & Ray, H. E. (2020). Perceived stress, work-related burnout, and working from home before and during COVID-19: An examination of workers in the United States [Manuscript]. PsyArXiv. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/vnkwa

11. Ingusci, E., Signore, F., Giancaspro, M. L., Manuti, A., Molino, M., Russo, V., Zito, M., & Cortese, C. G. (2021). Workload, techno overload, and behavioral stress during COVID-19 emergency: The role of job crafting in remote workers. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 655148. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.655148

12. Buomprisco, G., Ricci, S., Perri, R., & De Sio, S. (2021). Health and telework: New challenges after COVID-19 pandemic. European Journal of Environment and Public Health, 5(2), 1–5. https://doi.org/10.21601/ejeph/9705

13. Griffiths, M. L., Gray, B. J., Kyle, R. G., Song, J., & Davies, A. R. (2022). Exploring the health impacts and inequalities of the new way of working: Findings from a cross-sectional study. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 64(10), 815–822. https://doi.org/10.1097/JOM.0000000000002596

14. Wang, B., Liu, Y., Qian, J., & Parker, S. K. (2021). Achieving effective remote working during the COVID-19 pandemic: A work design perspective. Applied Psychology: An International Review, 70(1), 16–59. https://doi.org/10.1111/apps.12290

15. Sundermeyer, S. (2025). Time will tell: Working from home and job satisfaction over time. German Journal of Human Resource Management. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1177/23970022241310999

16. Oakman, J., Neupane, S., Kyrönlahti, S., Nygård, C. H., & Lambert, K. (2022a). Musculoskeletal pain trajectories of employees working from home during the COVID-19 pandemic. International Archives of Occupational and Environmental Health, 95, 1891–1901. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00420-022-01885-1

17. Xiao, Y., Becerik-Gerber, B., Lucas, G., & Roll, S. C. (2021). Impacts of working from home during COVID-19 pandemic on physical and mental well-being of office workstation users. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 63(3), 181–190. https://doi.org/10.1097/JOM.0000000000002097

18. Bosma, E., Loef, B., & Van Oostrom, S. H. (2023). The longitudinal association between working from home and musculoskeletal pain during the COVID-19 pandemic. International Archives of Occupational and Environmental Health, 96(4), 521–535. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00420-022-01946-5

19. Moretti, A., Menna, F., Aulicino, M., Paoletta, M., Liguori, S., & Iolascon, G. (2022). Characterization of home working population during COVID-19 emergency: A cross-sectional analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(17), 6284. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17176284

20. Messenger, J., Vargas Llave, O., Gschwind, L., Boehmer, S., Vermeylen, G., & Wilkens, M. (2017). Working anytime, anywhere: The effects on the world of work. Eurofound and International Labour Office. https://www.eurofound.europa.eu/publications/report/2017/working-anytime-anywhere-the-effects-on-the-world-of-work

21. Lauren Vercoe v Local Government Association Workers Compensation Scheme, [2024] SAET 91 (18 October 2024). https://www8.austlii.edu.au/cgi-bin/viewdoc/au/cases/sa/SAET/2024/91.html